Formally verifying AVX2 rejection sampling for ML-KEM

Formal verification of cryptography comes in many flavours. The levels of abstraction range from high-level protocol designs to machine-level implementations. At each level of abstraction, different target properties and formal verification technologies apply. In this post we look at the latter end of this spectrum and consider a highly-optimized architecture-specific implementation of a core routine of the recent NIST post-quantum standard FIPS-203: Module-Lattice-Based Key Encapsulation Mechanism (ML-KEM). For a more general overview of why formal verification matters in post-quantum cryptography, we refer the interested reader to the prequel blogpost available here.

The example we consider is representative of a class of highly-optimized routines that is typically written directly in assembly language, or using compiler intrinsics that give direct access to specific instructions. It therefore falls out of the class of programs for which typical software formal verification tools are designed. Indeed, the resulting code is very hard to relate to the specification of the functionality it is supposed to implement. We describe an approach to tackle this challenge, and achieve the ambitious goal of proving functional correctness for all possible inputs. The approach, deployed in the EasyCrypt proof assistant, combines different formal verification techniques and, in this way, it overcomes their inherent limitations when used in isolation.

This solution was recently presented at the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy 2025 [Almeida et al., S&P 2025]. The motivating example is an assembly implementation of ML-KEM for the AVX2 architecture which, on one hand, matches the performance of unverified code optimized for the same platform and, on the other, has been mathematically proven to be compliant with its specification, and to correctly mitigate timing side-channel attacks. This implementation is currently being prepared for deployment in Signal’s backend system for privacy-preserving contact discovery (this part of the story will be covered in an upcoming presentation at Real-World Crypto 2026).

Before we dive into the intricacies of the optimized implementation, let’s first recall some relevant details about ML-KEM, the Key Encapsulation standard specified in FIPS-203.

Generating a random-looking polynomial in Rq

The mathematics of ML-KEM revolves around Rq, which is defined as the polynomial ring Zq[X] / (X256 + 1) for q=3329. For the purpose of this post, we consider elements in this ring as arrays of size 256 containing 16-bit words representing unsigned values in the range [0,3329]. Optimizing ML-KEM implementations implies improving the performance of three types of operations over values in Rq and vectors/matrices with elements in Rq – the dimensions of such vectors and matrices are small (e.g., k=2,3,4) as is typical in constructions based on Module-Lattice problems. These are:

- Algebraic operations such as the Number Theoretic Transform, matrix and vector operations, etc.

- Serialization functions, including compression and decompression

- (Pseudo)random sampling

A particularly costly sampling operation results from a design choice in ML-KEM, which permits dramatic reduction of the public key size. Rather than including in the public key, a matrix A ∈ Rqᵏ×ᵏ, the public key includes a seed ρ ∈ ℬ³², a 32-byte random string that fully determines A. i.e., before one can encrypt to an ML-KEM public key, one must first recover A from ρ. The standard specifies the process of reconstructing A, one element in Rq at a time, in terms of a rejection sampling loop. One first initializes the SHAKE-128 eXtendable Output Function (XOF) with a seed that encodes ρ and the position in the matrix A, and then extracts (from the output of SHAKE-128) the first 256 sequences of 12-bits, which, when seen as unsigned integers, fall in the correct range [0:3329). The loop is unbounded, in the sense that it is left to run until all the necessary coefficients are found.

Assuming a pre-existing implementation of the SHAKE-128 XOF, implementing this rejection sampling procedure (and indeed, checking its correctness) seems straightforward. However, this assumption severely underestimates the creativity of cryptography practitioners in making the most of architecture-specific instructions to boost the performance of implementations. If we look at the AVX2 code for this rejection sampling routine in the available open-source implementations, we find a core routine that uses SIMD operations to batch-extract polynomial coefficients from the next 56-bytes in the XOF output in a fraction of the time taken by a naive implementation.

We reproduce below, a diagram of this code taken from [Almeida et al., S&P 2025] and refer the reader to the original text for a more detailed explanation and a discussion of the provenance of the ideas in this code.

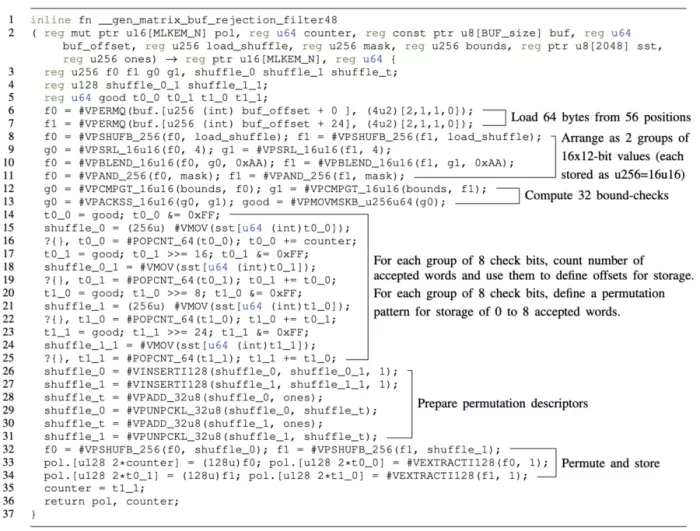

Annotated Jasmin code for the ML-KEM matrix generation

In short, the code first reads 48 bytes representing 32×12-bit candidates from the input buffer and rearranges them in two 256-bit registers as two 16×16-bit sets. Then the code checks the validity of all candidates in parallel and computes a 32-bit value that represents all the results. Then the candidates are processed 8 at a time: for each set of 8 candidates, a permutation descriptor is retrieved from a memory table (there are only 256 permutations for each set of 8 candidates). The selected permutations will place the accepted candidates on the left of each 256-bit register. Finally, the code computes the permutations, counts the good candidates in each set, and places them in the correct position of the output buffer.

This particular implementation is given in the Jasmin programming language, but the code itself can be thought of as assembly or a sequence of intrinsic calls in C as in the implementation available from the CRYSTALS-KYBER repository. Jasmin was particularly designed with formal verification of architecture-specific assembly code in mind. Specifically, in addition to certified compilation from Jasmin source to assembly, the Jasmin tool-chain enables extraction of a model of the program to the EasyCrypt proof assistant, where it can be analysed for arbitrary properties.

What can/should be proved about the code?

In general, for low level implementations such as this, there are three important classes of properties to check:

- Absence of undefined behaviour (or safety)

- Functional correctness

- Absence of timing leaks

We don’t intend to discuss timing leaks here due to the fact that this particular routine is usually assumed to perform only public computations. With respect to 1) and 2), it is typically the case (or should be) that checking for absence of undefined behaviors is part of the standard software development good practices. This is feasible with reasonable effort using tools such as Valgrind or, when stronger guarantees are deemed necessary, by deploying a tool such as CBMC, or Frama-C, for example, the approach taken in the mlkem-native project.

The extent to which functional correctness should be checked is not so clear. Of course, correctness can be checked by unit-testing and fuzzing, but is this sufficient?

Low-level code such as this can hide subtle errors that rarely manifest. Such errors are hard to catch and are known to give rise to vulnerabilities. Indeed, for security-critical applications, where the possibility of latent (intentional or unintentional) vulnerabilities must be excluded, the motivation for formal proofs of correctness is there. However, achieving such an ambitious goal may require significant resources, and this may be hard to justify. [Almeida et al., S&P 2025] propose combining deductive verification techniques to decompose the proof into manageable pieces, and circuit-based reasoning, where fully automatic proofs of equivalence can be performed, showing that full functional correctness can be proved with reasonable effort for the above routine.

Proof Intuition

The idea behind the proof techniques used to verify the implementation above, is that we can use deductive verification (a variant of Hoare logic, in this case exposed by EasyCrypt) to decompose the functional correctness goal into several sub-goals, each of which corresponds to a pattern that can be efficiently handled by using automatic provers for Boolean circuits, or simply SAT solvers. The crux here is that a blunt encoding into a circuit-based proof of the whole program as a circuit, will not necessarily work. We conclude this post by giving some intuition on why this is the case.

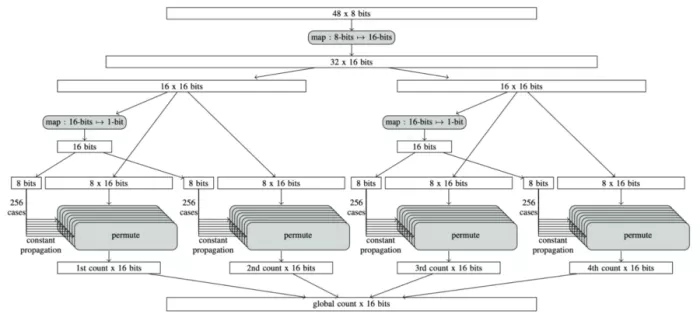

The diagram below, again taken from [Almeida et al., S&P 2025], illustrates how the program is broken apart interactively for the proof.

How the program is broken up interactively for the proof.

Downwards, the first step in the computation is expressed as a map computation from an array of 12-bit words to 16-bit words. In the original program, these 12-bit words are opaquely stored inside the input byte array. However, at the circuit level, one is free to choose any word size! This is one of the features of a new circuit-based reasoning backend that was added to EasyCrypt. Indeed, the proof that the 12-bit candidates are unpacked correctly to 16-bit words by a sequence of SIMD permutation instructions, is trivial once it is expressed at the circuit level.

Next, the computation of the range-check-bits for the 32 candidates can again be seen at the circuit level, as a map computation, now, however, mapping 16-bit words to 1-bit words. The computation in this case is slightly more complex, as it is not merely permuting the input bits. In this step, the proof showcases another optimization of circuit-based reasoning that was added to EasyCrypt: the ability to check the correctness of map computations by confirming that the circuit representing the implementation decomposes into parallel lanes, which are all functionally equivalent to each other (in fact they are syntactically identical, which means that the proof is usually trivial). As a result, functional correctness can be checked only for one of the lanes at a fraction of the cost.

Finally, in the most intricate part of the proof, the code uses memory tables for storing permutation descriptors. A naive implementation of circuit-based reasoning in this step would explode in complexity due to the need to encode data-dependent table accesses. However, by using the deductive reasoning in EasyCrypt, it is possible to automatically perform a case analysis of the 4×256 permutations, and, using constant propagation, completely eliminate the table accesses from the circuit-based goals. Crucially, the specification of the filter function itself reduces to a simple (partial) permutation once constant propagation is applied, which means that once more, the resulting circuit-based proofs for each case only need to justify straightforward bit rearrangements.

Take-away message

When discussing the formal verification of cryptography, there are many possible goals and a large body of super-exciting research work that is gradually making its way to enhancing the security of real-world systems. This is true at the design level, and it is also true at the implementation level. However, as discussed by Mike Dodds from Galois Inc. in this post, it is not always clear when and where the resources required by formal verification are justified, and this is particularly true for complete functional correctness proofs. However, for highly-optimized architecture-specific core routines such as the one we cover in this blog post, it is hard to argue that traditional testing and auditing mechanisms are sufficient to guarantee an adequate level of assurance. What our use case indicated is that the majority of these routines will be within reach of a formal verification approach that combines “brute-force” automation with high-level reasoning about program logics.

At PQShield, the technology described in this post is currently being used to formally verify core cryptography routines that take advantage of architecture-specific instruction sets and, in particular, that rely on cryptographic coprocessors. The goal is to ensure that functional correctness, and therefore security, is guaranteed even across these often challenging abstraction boundaries.

Explore Cryptography IP:

- Highly configurable HW Lattice PQC ultra acceleration in AXI4 & PCIe systems

- PQPerform-Inferno + RISC-V processor for enhanced crypto-agility

- Highly-optimized PQC implementations, capable of running PQC in under 15kb RAM

Related Semiconductor IP

- Highly configurable HW Lattice PQC ultra acceleration in AXI4 & PCIe systems

- PQPerform-Inferno + RISC-V processor for enhanced crypto-agility

- Highly-optimized PQC implementations, capable of running PQC in under 15kb RAM

- PUF-based Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) Solution

- APB Post-Quantum Cryptography Accelerator IP Core

Related Blogs

- Formally verifying protocols

- Formally Verifying Processor Security

- ML-KEM explained: Quantum-safe Key Exchange for secure embedded Hardware

- Integrating PQC into StrongSwan: ML-KEM integration for IPsec/IKEv2

Latest Blogs

- Silicon Insurance: Why eFPGA is Cheaper Than a Respin

- One Bit Error is Not Like Another: Understanding Failure Mechanisms in NVM

- Introducing CoreCollective for the next era of open collaboration for the Arm software ecosystem

- Integrating eFPGA for Hybrid Signal Processing Architectures

- eUSB2V2: Trends and Innovations Shaping the Future of Embedded Connectivity