Evaluating the Side Channel Security of Post-Quantum Hardware IP

Introduction

Deploying new secure cryptographic hardware isn’t just about implementing an algorithm; it’s about proving its security in practice. The definition of ‘security’ for new cryptographic IP implementing NIST’s FIPS-203 standard (ML-KEM) goes beyond the mathematical problem. A modern implementation must be secure against physical attacks, especially Side-Channel Attacks (SCA) and this security must be evaluated.

eShard provides a state-of-the-art evaluation suite, allowing partners to test and validate PQC algorithms against these hardware attacks. PQShield is a leading provider of post-quantum cryptographic IP, offering a portfolio designed to be secure against hardware attacks by default, including Embedded Software IP and Platform Security Hardware IP.

In this blog post, we demonstrate how we used the eShard evaluation suite to assess the security of PQShield’s ML-KEM IP against first-order side-channel attacks, one of the key steps to validate IP security. The main findings confirm the effectiveness of the implemented countermeasures against side-channel attacks in the IP.

Validating a protected IP

In an active collaboration, PQShield provided two versions of their IP implementing ML-KEM: a baseline unprotected version, and a protected version with SCA countermeasures. The goal was to challenge the side channel security of the protected IP.

To conduct the analysis, PQShield provided datasets containing power measurements recorded on their own SCA test bench, while eShard received only high-level information about the countermeasures. Following this, eShard performed a detailed analysis using their proprietary PQC module in esDynamic. The results were shared, and both teams collaboratively reviewed the findings.

Strategy

While PQShield validates the side channel security of its IP internally, using automated TVLA and ad hoc adversarial testing including DPA and template attacks, eShard provides a complementary evaluation strategy: the ‘Reverse method’.

The Reverse method excels in a black-box attack setting, in which the attacker has no access to detailed information about the implementation. It leverages knowledge of data processed by the device by correlating this data with the power traces. This allows it to learn about the IP’s leakage model and identify the secret-dependent operations an attacker would target – all without prior knowledge of the implementation’s details.

The attack paths developed by eShard as part of its PQC module were first validated on software simulations and then confirmed on physical devices. This generic approach has proven suitable for evaluating new attack methods. Usage of the Reverse method as a black-box tool provides a systematic search for the leakage model and selection functions.

IP Description

The target IP consists of a hardware accelerator for lattice-based cryptography with associated RISC-V firmware. It integrates protections against SCA, primarily through arithmetic and boolean masking, and uses mask conversions to switch between these domains. Additionally, hiding countermeasures are implemented on top of the masking in order to further reduce the effectiveness of high potential SCA attacks. Hiding techniques aim to increase the amount of noise and to dissimulate the location of the target operations within the power trace. To avoid trace misalignment, some of the hiding countermeasures within the IP are turned off during trace acquisition. Based on the implemented countermeasures, the IP is expected to resist first-order SCA.

A separate, unprotected version of the implementation is used in order to validate the attack methods. This implementation uses the same hardware building blocks for the computation of polynomial arithmetic as the protected version, but it does not contain any masking or hiding countermeasures. The unprotected implementation is not designed to be resistant against SCA.

Trace set generation

The IP is loaded on the FPGA of a CW305-A100 FPGA development board, which is connected to a host PC. This PC uses a Python library to generate keys and inputs for the decapsulation, and to communicate with a Picoscope 6000 oscilloscope. The target runs on a frequency of 50 MHz, with the oscilloscope collecting 625 million samples per second. The setup captures power traces without any misalignment in the collected trace sets. In order to keep the size of the trace set in memory in check, the power traces record only the computation of the point-wise multiplication between the first polynomial of input ciphertext u and secret key s. This operation is typically the first target in a DPA (Differential Power Analysis) on ML-KEM.

Metadata labels are associated with each captured trace, specifying the values of the coefficients of the first polynomial of u and s. The input ciphertext is randomly generated for each trace. For both the unprotected and protected implementation, two separate trace sets are generated. The first set uses random secret keys (s), destined for leakage analysis, while the second set uses a fixed secret key to simulate a real world DPA scenario.

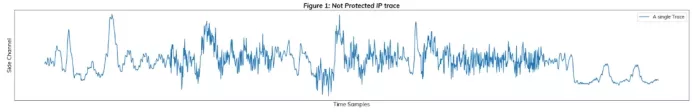

Figure 1: a trace acquired with ChipWhisperer of the unprotected version of the IP, executing an ML-KEM-512 Decapsulation with a random ciphertext

eShard PQC Content

With the aim of bringing the evaluation of PQC implementations against side-channel attacks closer, eShard has developed the PQC expertise Module. Its goal is to provide essential knowledge about recent post-quantum cryptographic algorithms, such as ML-KEM, and their side-channel and fault-injection vulnerabilities. The module intends to achieve its goal by the following means:

- First, the module provides thorough explanations of the algorithm construction and underlying mathematics, with detailed descriptions, graphical representations, and simplified Python implementations.

- Second, the module offers an executive survey of principal side-channel attacks on unprotected implementations of NIST’s PQC candidates.

- Third, it provides datasets for practical side-channel analysis using eShard’s simulation tracing tool esFirmware. The simulations are aimed at ARM targets with freely available PQC candidate implementations, in the context of embedded systems. These datasets serve as material for the fourth and ultimate goal – a series of attack notebooks, where the different attack targets and related techniques are explained in detail.

- Finally, through tutorials, how-to guides, and use-case Python notebooks, eShard provides reusable and editable support to address attacks and characterization methods applied on PQC candidates selected as NIST PQC standards. Such attacks are applied on the simulated traces obtained using esFirmware. For example, a user of the module can perform all the steps to run a First-Order Correlation Power Analysis on an ML-KEM implementation. Using state-of-the-art techniques, the attack is refined to reduce the number of key hypotheses, and parallelized efficiently with multiprocessing.

Characterization

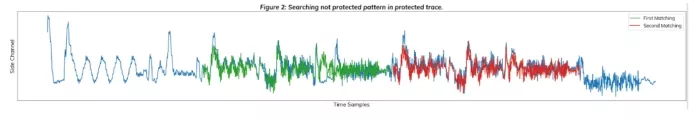

To identify the countermeasure validating the protected traces, we searched for similarities between a) the traces from the protected implementation and b) the traces from the unprotected implementation. A classical approach is to identify high-level patterns and find by correlation, the parts of the unprotected traces within the protected traces. Figure 2 shows that there is a repetition of similar activity in the protected traces. At this point, the countermeasure might be either a first-order masking or the execution in random order of two operations, one with random data, the other with the real data. We keep these two assumptions in mind and continue our analysis.

Attack Analysis

Analysis of the unprotected implementation

As a step further, one might try a reverse analysis on a device, in order to characterize its leakage. A reverse analysis works in the same way as an attack, but in this case we know all the intermediate variables we want to target. The steps for such an analysis are as follows:

- Obtain power (or EM) traces of the analyzed devices, annotated with critical intermediate variables as metadata.

- Choose a selection function that operates on the intermediate variables. Subsequently, for the sake of conciseness, we selected one of them : the result of modular multiplication between a coefficient of the ciphertext and a coefficient of the secret key in the NTT domain (uo[i] * so[i] mod q).

- Apply a leakage model on the result of the selection function for all the traces. Again, to keep it short, we present here only a result with the Hamming Weight Model.

- Use a statistical tool to obtain a score on the leakage. We used Pearson’s Linear Correlation.

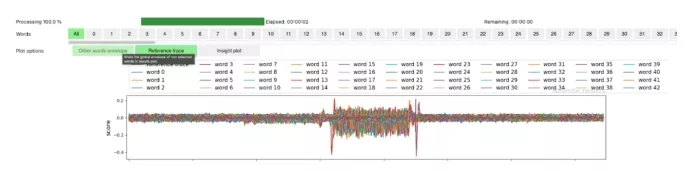

For example, the following shows the result of one of the reverse analyses on the unprotected implementation:

Leakage is well observed and the polynomial multiplication area is well identified. We may have a good chance of success in the attack, if we do not observe high peaks on the incorrect hypotheses.

We select the best results and attempt to observe whether an attack would work, considering all the possible hypotheses for each coefficient of the secret key. For efficiency, we target the area identified in our reverse analysis that yields good results of correlation for each word. Below, we show the result of the attack for the first eight words.

We can see from the convergence graph that we need a small number of traces (around 100) in order to succeed for word number 3. Other targeted words were obtained with a similar number of traces. This validates the capability to extract the whole key from the leakage. Armed with our analysis and result of attacks on the unprotected implementation, we can investigate the resistance of the protected implementation to a first-order leakage.

Analysis of the protected implementation

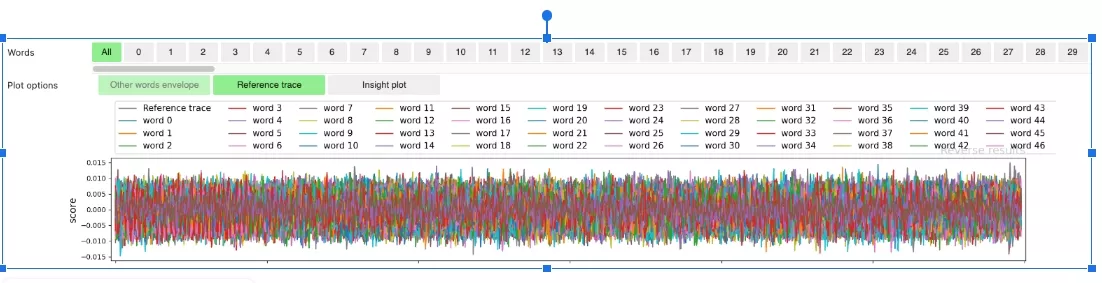

By construction, the protected implementation internally generates the random values used for the masks. The reverse analysis is made impossible so that we rely only on attacks to validate the resistance of the protected implementation. Several attempts were performed to find first-order leakage despite the presence of countermeasures – none of them leading to any private key coefficient recovery. As illustrated below, with the protected implementation, leakage characterizations do not highlight any point of interest.

We can now discard the assumption that the implemented countermeasure corresponds to the shuffling of two instances of ML-KEM in a random order. Indeed, in the presence of shuffling, the leakage of unprotected implementation is so strong, that our analysis should have shown peaks at the places of the two executions handling unmasked data.

Despite the lack of point of interest, we performed several attacks focusing on the entire trace. The following figure illustrates one of the results we observed. This result is representative of all first-order attacks conducted. Even if we focus on the locations of leakage identified with the attack on the unprotected implementation and translated to the protected one, none of our analyses on the protected implementation, even with Mutual Information Analysis (MIA), resulted in recovery of private key coefficients.

Conclusion

PQShield routinely validates the resistance of its IP designs against SCA, with a TVLA approach that is optimized to detect first-order leakage. eShard’s preferred method consists of a two step analysis. In the first step, a deep analysis of an unprotected implementation of the IP is performed, where leakage models and effective selection functions are qualified in regard to the exploitation of the leakage. The exploitation is confirmed with attacks recovering the whole key coefficients when countermeasures are disabled. The second step focuses on the protected version of PQShield ML-KEM IP with countermeasures enabled. The leakage analysis evidenced the presence of a masking countermeasure, since no leakage can be observed with 1000 times more traces than required for the unprotected version. Despite the knowledge collected on the unprotected version, no first-order attack successfully extracted the private coefficients of the key of the SCA-protected IP. The results confirm that the two validation methodologies by PQShield and eShard lead to analogous results in demonstrating first-order side-channel resistance. However, as usual, this is only a first step of validation. eShard regularly adds new attack techniques to its PQC module, and will continue to collaborate with PQShield to push the analysis to second-order – obtaining increasing confidence on the resistance of the protected version. The collaboration includes the sharing of executable notebooks created by eShard for this investigation, which can be reused by PQShield for further analyses. Together, we have already conducted preliminary leakage analysis with second order techniques, and at the current time we do not observe leakage in sight. In any case, only first-order SCA was our focus for this first analysis and there is another level of complexity to be considered.

Related Semiconductor IP

- PQPerform-Inferno + RISC-V processor for enhanced crypto-agility

- ML-KEM Key Encapsulation & ML-DSA Digital Signature Engine

- Post-Quantum ML-KEM IP Core

- xQlave® ML-KEM (Kyber) Key Encapsulation Mechanism IP core

- ML-KEM Key Encapsulation IP Core

Related Blogs

- Quantum Safe IP: Hardware Level Security for the Quantum Computing Era

- Ensuring IoT Security Against Side Channel Attacks for ESP32

- The Evolution of CXL.CacheMem IDE: Insights into CXL3.0 Security Feature

- Trust at the Core: A Deep Dive into Hardware Root of Trust (HRoT)

Latest Blogs

- Silicon Insurance: Why eFPGA is Cheaper Than a Respin

- One Bit Error is Not Like Another: Understanding Failure Mechanisms in NVM

- Introducing CoreCollective for the next era of open collaboration for the Arm software ecosystem

- Integrating eFPGA for Hybrid Signal Processing Architectures

- eUSB2V2: Trends and Innovations Shaping the Future of Embedded Connectivity