Platform Software Verification Approaches For Safety Critical Systems

Nirav S Patel, Sr. Software Engineer, eInfochips

Abstract

Innovation is the key to surviving the rapidly changing world of embedded electronics. Efficient testing is a crucial step to achieve the design of reliable products. Emerging applications be in aerospace, automotive or industrial automation systems, need to be tested thoroughly and rigorously. Consequently, in this paper, we shall discuss various techniques to verify DO-178B LEVEL A platform software [5]. The software platform consists of software pieces for hardware interface, operating systems and protocol/standard API libraries. We shall discuss possible platform software verification techniques and solutions including their merits and demerits in safety-critical systems based on eInfochips client experience in aerospace, defense and automotive systems. In general, a single technique doesn’t work for all scenarios and a mixture of different approaches make it possible to robustly and rigorously verify the platform software.

Introduction

A general prevailing wisdom is that “verification requires 70% effort” in the overall software life cycle. Indeed, verification is a key phase in the software development life cycle. Due to the very competitive nature of embedded systems in software industries around the world, each and every software life cycle phase experiences increasing pressure of schedule and costs. Moreover, delays and issues in an earlier software life cycle phase increases pressure on the last phase, of-course through verification and validation.

Today, a lot of verification tools are available in market (open source/free/license-based) for traditional software verification which can potentially speed ahead software testing. It becomes more challenging to verify the platform software using the traditional software verification tools because of a variety of operating systems and hardware platforms. A platform software verification framework methodology has a variable approach based on hardware and operating systems. The verification approaches can also vary due to growing complexity of requirements and design dependence on very low level hardware-specific details.

In this paper, we will attempt to provide some common verification techniques and approaches for efficiently verifying platform software across different operating systems and H/W platforms.

Platform Software Components:

What is platform software? It is a major piece of software code that manages a system’s hardware and software resources while providing common services for applications programs.

Platform software includes different components as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Basic Architecture of Platform Software Components

- Boot: It runs when the system starts and it is responsible for launching the operating system.

- BSP/CSP: It is represented by board/chip support packages which include interface functionalities between CPU, hardware peripherals and operating systems/device drivers.

- Static device driver [1]: These types of device drivers are part of the operating system package, which are installed during the boot-up process. e.g. RS232, I2C, PCIe.

- Dynamic device driver [1]: These types of device drivers can be installed in run time. e.g. Wi-Fi, SATA, USB, file systems.

- Libraries: These are the packages of functionalities exposed by platform software which can be used by application software or other platform software components.

Platform Software Verification Approaches

Software modules designed for LEVEL-A need to be verified across each and every line of source code against requirements to meet stringent DO-178B objectives in aerospace industry.

Major platform software components reside at kernel level. Largely, verification of this low level software is done through user level test software for various reasons such as automation, reusability, portability and simplicity of test code. The subsequent sections in this paper describe techniques/approaches along the same line. Here we discuss various platform software verification techniques:

[A] Test Application:

This is one of the least sophisticated approaches among various platform software verification approaches. This is widely used across all the levels of software modules. The device drivers are accessed through well known entry points (Open, Read, Write, Ioctl, Close). All the entry points related to functional requirements can be verified by calling upon the entry points from the test application.

Figure 2: Test Application based Platform Software Verification Approach

As shown in fig.2, test applications call upon the entry points of the device drivers while verifying their expected functionality.

Pros:

- This is the fastest and simplest approach to verify the high level requirements of the device drivers

- It verifies the normal functional aspects of the device driver

- This approach is useful in testing the dynamic and static driver entry points (except install) functionality

Cons:

- This approach is not suitable for the platform software components which are only accessible within the kernel space.

- This approach might not satisfy all the aspects of verification for LEVEL-A/B device drivers where 100% structural coverage of source code is essential.

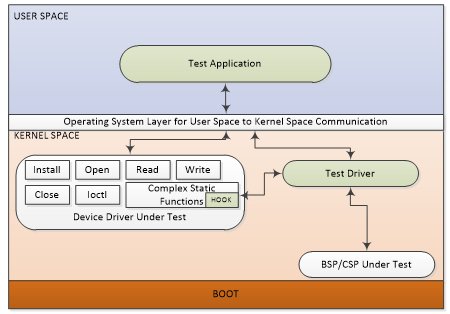

[B] Test Application with Test Driver:

Applications can’t access the kernel space functionality but device driver inserted in kernel space can access the global functions and global variables or data structures in the kernel space. By inserting the test driver, kernel space functionality can be indirectly made available to the test application.

As shown in Figure 3, test application verifies the device driver and BSP/CSP functionality by routing the call through test driver.

Figure 3: Test Application with Test Driver

Pros:

- Kernel level functionality is not directly exposed to userspace applications and can be tested through the test driver.

- A static device driver’s install entry points are called on the boot-up process to be tested through the test driver.

- Complex device driver functionalities which are globally accessible in kernel space can be tested through the test driver.

Cons:

- Test application with test drivers cover the functional verification aspects but might not cover the robust and abnormal scenarios where failure conditions needs to be induced during testing.

- This approach might not satisfy all the aspects for the verification of LEVEL-A/B device drivers where 100% structural coverage of source code is essential.

[C] Test Application with Test Driver and Stub Driver:

Stub concept is used to isolate the functionality under test with the rest of the system functionality. The stub concept is very useful for unit testing based on low level requirements wherein the functionality input can be simulated to verify the behavior of the source code as show in Figure 4.

Platform software mostly relies on hardware and OS APIs. During normal operations, verification engineers can’t introduce different kinds of hardware failure, unexpected hardware events or different OS input/output to perform robustness tests. Stub on hardware write or read APIs and OS kernel/user space APIs can make the verification engineer’s life easy in terms of simulating a variety of verification conditions.

Let’s see a few examples where the stub technique can be used. A test objective is used to verify the behavior of the device driver under test, wherein I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) bus transaction fails to read/write data from the I2C connected device. Hardware transaction does not fail in the normal condition, and is difficult and costly to introduce faults in hardware. However, the hardware failures can be simulated in software by stubbing the I2C transactional control/data read/write register APIs. Similarly, other OS/BSP functionalities can use stub technique to generate robustness test conditions. (e.g. malloc(), kmalloc(), register_dev() etc…)

Figure 4: Test Application with Test Driver and Stub Driver

Stubbing can be performed with different methodologies. For the platform software, the following stub methods can be used for runtime on target.

- Symbol Table: A symbol table maps machine codes (instructions) in the compiled binary to their corresponding variables, functions, or lines in the source code. This mapping looks like: Machine codes (Instructions) ⇒ item name, item type, original file, line number. Symbol tables may be embedded into the executable program code or stored as a separate file. So, by modifying the symbol table’s information, function calls can be re-routed to the test-stub functions. They are also known as cheating symbol files [4]. The verification stub mechanism needs to parse the symbol file (COFF format [3] or ELF format [2]) to achieve symbol stubbing.

- Glue Logic: Normally, symbol files are not embedded or provided with the certification/production build binaries on the target environment. The executable code of the programs is stored in the “.Text” memory section which use function/symbol addresses resolved by linker and loader. By modifying function first instruction (mnemonics) with the jump instruction to stub function, the function call is rerouted to stub function. But “.Text” section is a read only memory. Any run time change in the “.Text” memory section can throw processor exceptions out of gear. The following steps for the glue logic can help implement the intended stub functionality for the PowerPC core.

a. Calculate the Address offset between Original Function and Stub Function

b. Prepare Jump (Branch) instruction (mnemonics) based on the selected platform for calculated offset

c. Disable Memory Management Unit

d. Replace the First instruction located at Original Function with Prepared new instruction

e. Enable Memory Management Unit

Pros:

- Test applications with test driver and stub driver cover robust and abnormal scenarios where failure conditions needs to be simulated for the testing.

- This approach covers the structural coverage for complex device drivers.

Cons:

- This methodology may not help to generate robust and abnormal test conditions for very complex low level requirements typically implemented by platform software with no visibility to outer world. (e.g. static variables and static functions).

[D] Test Application with Test Drivers and Hook Functions

In the software world, Hook definitions vary a lot. Here, hook function means injecting the test code in the source code of the platform software component under test which can provide access to the internal variables and functions of device drivers to the test application or test driver to simulate the different conditions. Typically, the hook is implemented as a function pointer. The test function can be registered with test hook functions to simulate the verification conditions. Wisely inserted hook functions do not impact the actual source code functionality and it can be enabled or disabled run time based on the verification commands. Hook functions can be added as tags in the development of the source code.

Hook methodology is a white box testing methodology used for verification of low level software requirements which have tricky implementation details which cannot be described as easily as their functional requirements.

Figure 5: Test Application with Test Driver and Hook Functionality

Pros:

- White box testing is possible to reach out to low level internal implementation specific requirements using hooks. (e.g. For the Boot software, mostly none of the previously described verification approaches are useful, and Hook approach can help verify low level Boot software implementation as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Hook Method to test the BOOT

Cons:

- The platform software source code under test needs to be modified which needs to be justified for safety critical systems.

[E] Hardware or Software Debugger

In this verification approach, the debugger is connected with target wherein source code under test is running. By planting breakpoints and altering the memory (variable) contents, different scenarios can be created and intended functionality tested. Nowadays, most of the debuggers support GDB commands and Python/TCL like scripting languages. Using such features, verification engineers can develop test scripts which have a sequence of debugger commands to automate the testing. This method is useful for unit testing and debugging the development time issues, but is less popular as a formal verification method.

Pros:

- In the test conditions where none of above verification approaches are applied, the debugger approach can be used to simulate the verification condition. e.g. To verify the boot. (* it is same as “Test Application with Test Drivers and Hook Functions” approach)

Cons:

- This approach might not be used where multi-tasking software is under test. Because breakpoints stop the task execution with unpredictable behavior when other tasks executions depend on the task under test.

- This approach might not be useful when performance related functionalities need to be tested.

Platform Software Verification Framework

All the above approaches coupled with Host side software tools communicating over typical interfaces (such as network, serial, USB etc.) makes an automated platform software verification framework solution.

As shown in the Figure 7, Target is running with Test Application, Test Driver, Stub Driver and Hooks are controlled through “Verification Framework Controller” from the host. The following advantages of the platform software verification framework are mentioned below.

- Portable & reusable test scripts/code across different platforms

- Reduce time and cost of platform software verification test case development

- Automated testing without user intervention running from Host

- Ability to easily debug failures from host PC through verification framework

- Consolidated result logs on host without storage constraints

- Easy to customize Host based Test Report generation as per need and integration with other tools

Figure 7: Platform Software Verification Framework Solution

Conclusion

We looked at individual verification approaches: test application, test driver, stub driver, hooks and debugger. There is no single technique or approach to verify all platform software components for safety critical systems. One needs to apply multiple techniques to be able to verify platform software robustly & rigorously and meet stringent verification objectives.

In meeting demanding schedules for, especially sensitive industries like aerospace and military applications, a platform software verification framework supporting multiple techniques described earlier is the solution without letting go the quality for safety critical systems.

References

[1] Linux Device Drivers by Allessandro rubani and Jonathan corbet published by O’Relly & Associates Inc.

[2] http://www.skyfree.org/linux/references/ELF_Format.pdf, elf file format

[3] http://www.skyfree.org/linux/references/coff.pdf, coff file format

[4] https://grugq.github.io/docs/subversiveld.pdf, Cheating ELF File

[5] RTCA/DO178B, “Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification”

Related Semiconductor IP

- NPU IP Core for Mobile

- NPU IP Core for Edge

- Specialized Video Processing NPU IP

- HYPERBUS™ Memory Controller

- AV1 Video Encoder IP

Related White Papers

- Platform Software Verification Framework Solution for Safety Critical Systems

- A RISC-V Multicore and GPU SoC Platform with a Qualifiable Software Stack for Safety Critical Systems

- Efficient methodology for design and verification of Memory ECC error management logic in safety critical SoCs

- Hardware-Assisted Verification: Ideal Foundation for RISC-V Adoption

Latest White Papers

- Breaking the Memory Bandwidth Boundary. GDDR7 IP Design Challenges & Solutions

- Automating NoC Design to Tackle Rising SoC Complexity

- Memory Prefetching Evaluation of Scientific Applications on a Modern HPC Arm-Based Processor

- Nine Compelling Reasons Why Menta eFPGA Is Essential for Achieving True Crypto Agility in Your ASIC or SoC

- CSR Management: Life Beyond Spreadsheets